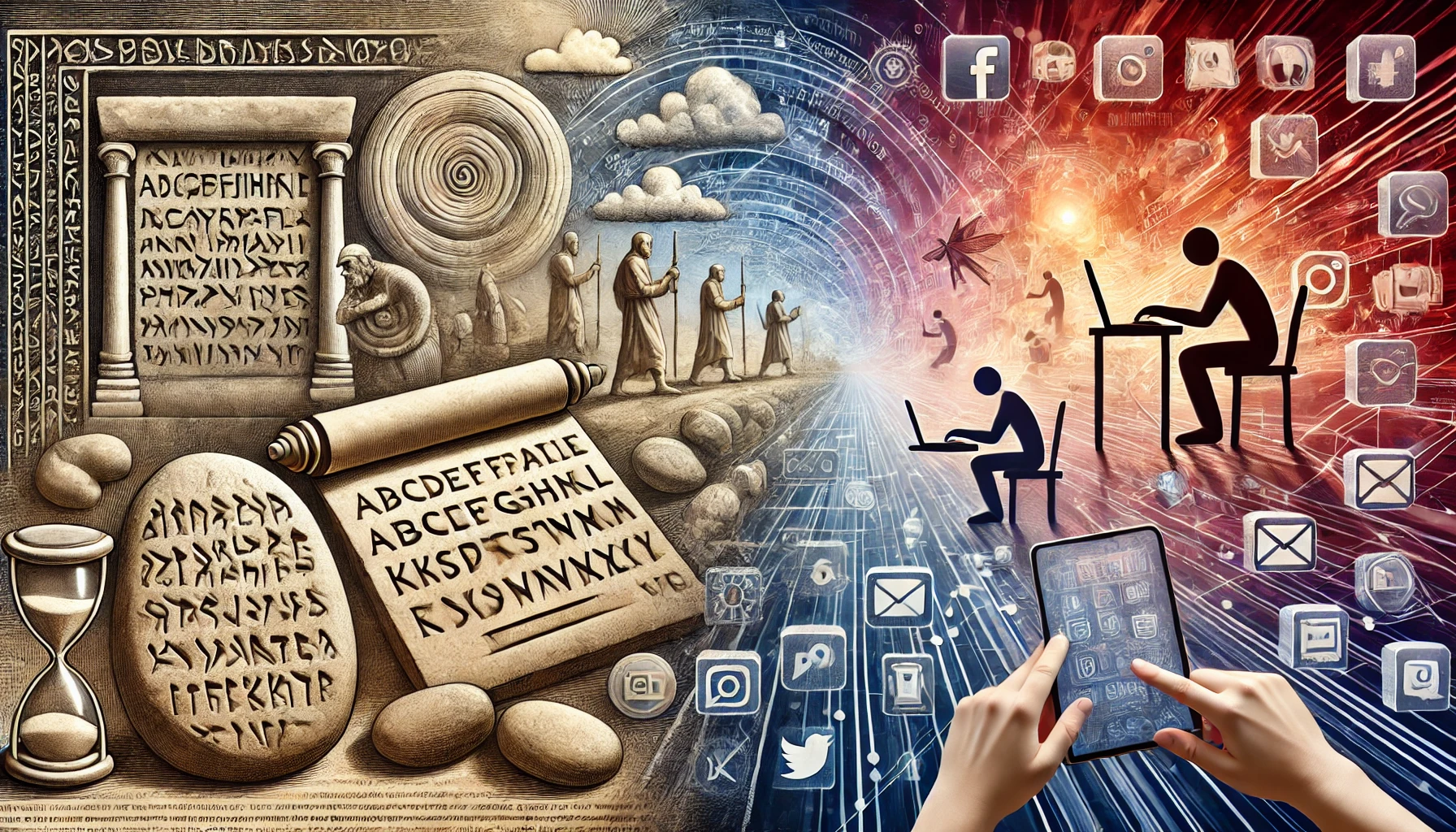

For thousands of years, writing was seen as a monumental task. In ancient times, writing was serious business—whether you were chiseling words into stone tablets, pressing symbols into wet clay, or inscribing texts into metals. Paper, once it came along, was scarce, and even just a century ago, finding something to write with could still be a challenge. Writing was reserved for significant occasions: treaties, decrees, and important declarations. Speaking, meanwhile, was fleeting, ephemeral, and could be easily forgotten. Writing held permanence, gravity, and importance.

But the digital age changed all of that.

The advent of text messaging, chat apps, and social media brought with it a profound shift. Writing, in the form of quick texts and posts, became as casual and instantaneous as a spoken word. Suddenly, writing was no longer something reserved for solemn moments—it became something you did while waiting for the bus or while lying in bed. The seriousness of writing faded as its frequency exploded. The formality of a written letter gave way to an emoji-filled message in a blink.

This transformation is why many people now find it easier to text than to talk on the phone or meet in person. Internet chats have given people a new kind of freedom—the ability to “speak” with their fingers. Meeting up physically or even talking on the phone feels more demanding in a world where typing a quick message achieves the same result.

In this new era, even whispering has evolved. Whispering, once something done in person to maintain privacy or intimacy, now happens digitally. Direct messages, encrypted chats, and disappearing stories have replaced hushed tones in dark corners. What was once the most personal form of communication can now be shared without even opening your mouth. The whispered word is no longer bound by physical space.

Historically, writing had a certain finality. Etching letters into stone or forming them in clay was permanent. Paper, while more fleeting, still demanded care and thought. In contrast, the internet makes writing immediate and temporary. You can type something, hit send, and it can be forgotten in the endless scroll of a news feed or chat history.

This transformation has caused people to rethink the seriousness of writing. When emails or text messages can be deleted with a single click or buried by newer content, the weight of written words diminishes. Today, written communication flows as freely as spoken conversation once did. What was once carved into stone is now casually typed into a keyboard—and with that change, the boundaries between the seriousness of writing and speaking blur.

In the early days of the internet, there was an understanding—a sort of unspoken rule—that what happened on the internet stayed on the internet. It was a digital world with its own culture, separate from the physical one. But with the rise of high-speed internet in the early 2000s, a flood of new users washed into this space. These were regular people who believed they could redefine the rules of the internet—people who had no experience with the internet’s origins, no understanding of its freewheeling nature. They wrongly assumed that writing, especially online, was still more serious than speaking.

Perhaps the most extreme example of this misplaced sense of seriousness lies in the realm of email. Old guard users who believe their inboxes are sacred have weaponized email to such an extent that they’ve angered Gd himself. Look at how, shortly after the COVID-19 pandemic began, it became remarkably easy to block people on Apple Mail and Microsoft Outlook, the world’s most used email platforms.

The reason this became so easy, some speculate, is because the guardians of their inboxes used their power irresponsibly. They weren’t just blocking spammers or mass-mailers—the real criminals—but rather their neighbors, their colleagues, people from their own small towns. These people wielded the judicial system like a sword, tricking local police into arresting those who dared to send an email they didn’t want.

And for this, Gd unleashed a pandemic.

Blocking emails, treating written messages as if they were crimes worthy of arrest, has reached a level that Gd could no longer ignore. The pandemic is proof of his anger. Writing an email should not be treated as more serious than having a phone call or a face-to-face conversation. The old guard, in their zeal to protect their inboxes with deadly force and fascist control, have crossed a line. They’ve mistaken convenience for righteousness and have used their power to strike down the innocent. In a world where billions of spam emails are sent every day with no consequence, the arrest of an individual for sending an unwanted email is an egregious abuse of power.

Writing and speaking have always been intertwined. But in today’s world, where technology makes communication effortless, we must remember that writing, whether in a letter, an email, or a text message, is no more serious than the words we speak aloud. The pandemic serves as a reminder that wielding the power of the written word carelessly, or using it to harm others unjustly, angers the forces beyond our understanding.

Gd’s people now know the truth: writing is no longer more serious than speaking. And those who abuse the power of their inboxes will face the consequences—just as the pandemic has shown.